Growing up in Nigeria ensured that entrepreneur Dolapo James developed an appreciation of patterns and textiles at a very young age. “My parents, grandparents and I all wore patterned fabrics as casual clothes,” she explains. “My grandmother even sold printed fabrics for a while, so those patterns have always been part of my life.”

Dolapo moved to England at the age of 17 to take her A-levels and then went on to go to university in Nottingham to study architecture. “While I was studying I made bags, scarves and purses in vibrant African fabrics. I love the idea of a tote bag or clutch introducing a little bit of colour pop to a plain outfit.” She explains that most of these fabrics come in six-metre lengths with the patterns printed as huge motifs. “Each accessory offers the chance to own a small piece of a work of art, like a jigsaw.”

“My parents, grandparents and I all wore patterned fabrics.”

Dolapo James

As Dolapo sold her accessories online at Etsy and at markets and fairs, she found that people were always asking questions about the fabrics and prints, wanting to know where she’d sourced them from. “They were intrigued by the fabrics – a lot of my accessory customers are creative people who have their own ideas about how they would use the fabrics, if only they could find them.” The answer, Dolapo soon realised, was obvious, and late in 2015 she launched her fabric business, Urbanstax.

The history of one of Africa’s famously colourful wax print fabrics is far from straightforward, but Dolapo believes that this varied heritage is part of the appeal of these unique textiles. "These were originally attempts at copying and mass producing Indonesian batik fabrics, which it is believed, the Dutch tried to trade in Europe, but no one was interested,” she exclaims, “So the Dutch took them to the African market, and they became really popular!”

This month, we're exploring the craft heritage of some of our favourite crafts to celebrate Black History Month. We'll be talking to inspiring designers and makers whose work is interwoven with traditional craft techniques. This interview was first featured in Simply Sewing magazine and is kindly reproduced here on Gathered with thanks to Dolapo James.

Before long, manufacturers in African countries began to produce their own versions of the prints, bringing their own interpretation to the surface designs and changing them over time to incorporate traditional symbols. “I love the way it all weaves together,” Dolapo enthuses. “African fabrics are actually world fabrics, with histories from more than one country and continent.”

Traditional stories

The narratives added into the prints by women in Nigeria, Ghana, Gambia and other African countries are particularly enticing and inspiring to Dolapo. “I’m intrigued by the stories behind the fabrics and am always asking my grandmother and other people in the community what all of the different motifs mean.”

Her first step in setting up her own fabric business was sourcing the producers that use traditional techniques. “Nigerians are very entrepreneurial, so I find a lot of people on Instagram where they post about what they’re doing,” she says. “I’ll go to see them when I’m home visiting family. Nigeria and Ghana are only an hour’s flight apart, which helps.”

Dolapo also takes the opportunity to visit markets with an eye open for producers of quality fabrics, and drops by factories to scope out manufacturers. "While batik is done by hand, print is carried out on a more industrial scale. I'm always on the look out for new sources."

African fabrics are actually world fabrics, with histories from more than one country.

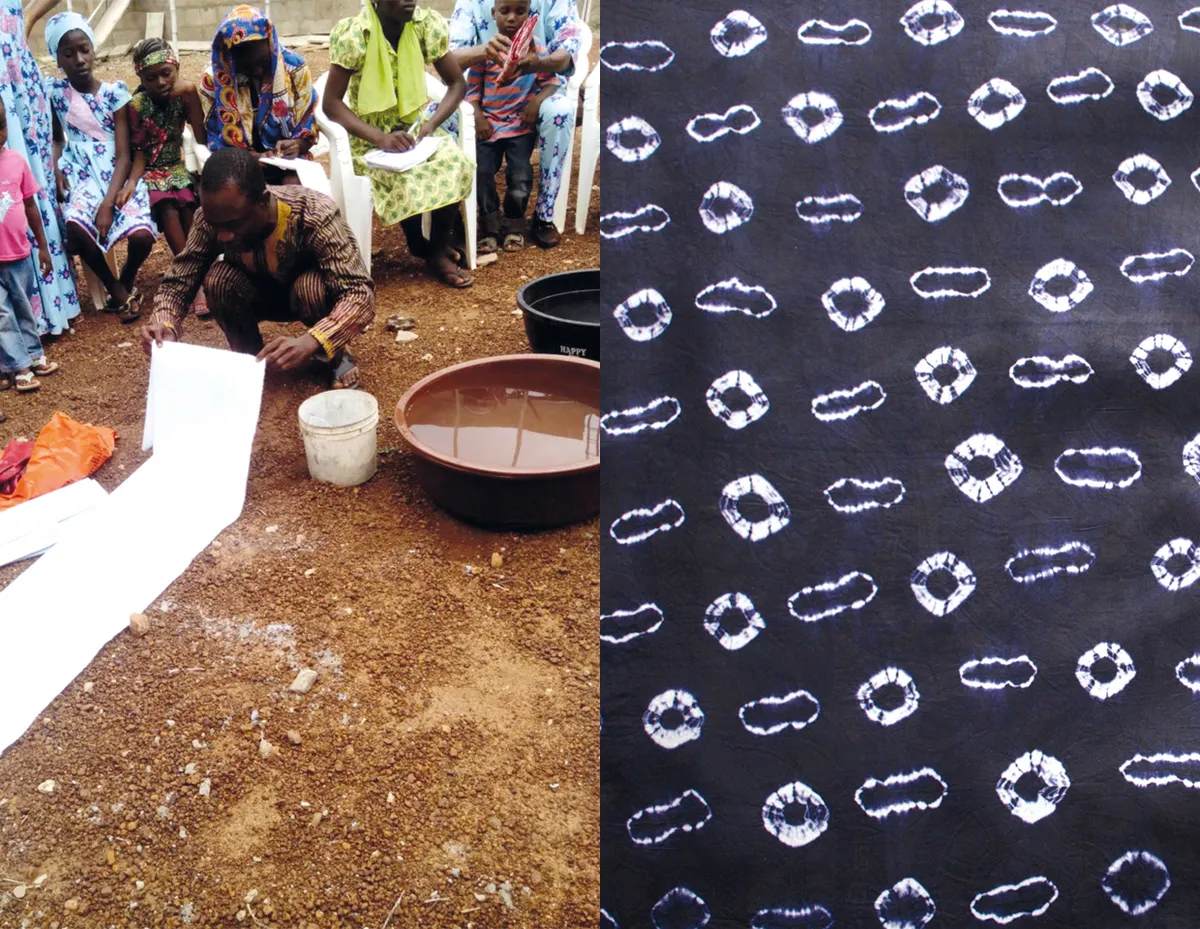

One fruitful source has come via textile designer and artist Nike Davies-Okundaye. “Mrs Okundaye is well known for promoting art, handmade and local crafts in Nigeria including the Adire technique, and doing her best to keep it alive,” says Dolapo. “She set up training facilities to teach young people how to make batik fabrics. Nigeria has a huge population and high unemployment. Finding a job often isn’t easy, even if you have a degree, but Mrs Okundaye’s training offers skills they can use to earn money.”

Dolapo explains a few of the time honoured batik techniques. “Adire is a tie and dye method used by the Yoruba women of Southern Nigeria. The fabric is threaded, pleated or tied before dyeing, leaving white patterns where the fabric has been tied. Dolapo seeks out graduates from Mrs Okundaye’s courses.

It isn’t easy to fight off competition from markets such as China, however. “Even in Nigeria, people are used to buying cheap knock-offs that are just imitations of traditional designs,” says Dolapo. “They’re infringing on copyright, and have no idea of the meanings behind the motifs that they are stealing. Plus, the fabrics they make don’t employ anyone in the local economy, which is such a waste.”

Dolapo’s big challenge is convincing consumers that her fabrics are a worthwhile investment. “The money goes to the actual designer and maker, which is important to me,” she says. “The textiles are 100% cotton and can be washed again and again. My grandmother has items made from fabrics just like the ones I sell that she’s had since before I was born and they still look as good as new.” Dolapo cherishes the thought that through buying one of her fabrics, you come to “own a little piece of history. The meanings are so interesting. For example, one motif means ‘A worthy woman is the crown of her husband.’ Older people in Nigeria can read them like little proverbs.”

A global village

In the past these designs would have been painted as murals on the walls of homes or carved onto wooden dishes. “By printing them on fabrics and then sewing these into garments or accessories, we’re using traditional patterns in modern ways.”

For Dolapo, a large part of the appeal involves bringing together old and new handicrafts and cultures from across the world. “I’m living in Watford, England, sourcing fabrics from African countries and selling them to customers in countries all over the world,” she enthuses. “This morning I had an order from Australia!” At the Knitting & Stitching Show in October 2016, Dolapo met with a customer who had a beautiful top made in shibori fabric – a Japanese batik technique. “It was in the most gorgeous blue, and she found a Ghanian print fabric in the same blue on my stand,” says Dolapo. “She’s going to use it to make sleeves for the top, so it will be a wonderful mix of cultures.” Meeting her customers is a genuine perk of the job for Dolapo, who relishes seeing her passion for her textiles and patterns shared by other talented sewists. “I’ve started a blog on the Urbanstax website about the people who have made lovely things from the fabrics,” she says. “I invite my customers to send me photos of the things they make. I enjoy these fabrics so much, and it’s nice to see what people are creating from them, and how much enjoyment they’re getting too.”

I remember marvelling over that as a child, how everyone knew what to wear when.

When she attends events such as craft shows, Dolapo puts up a wall full of photos of the wonderful things people have turned her fabrics into. “A woman made amazing curtains for her home in Israel, and a guy made a shirt for a visit to Cuba, and sent me a photo of himself wearing it in front of a vintage car in Havana.”

Upcoming travels of her own will include, she hopes, fabric-sourcing trips to other parts of the African continent. “So far I have only been to Western Africa, because that’s where my family are, but I’d love to go to Tanzania, Kenya, Somalia and so many other countries. Each one has its own history and original stories. I would like to have an even more varied selection of textiles for people to buy and learn about.”

She isn’t yet ready to stop investigating her own textile heritage, however. “Last May when I went home, my mum had a surprise for me,” she says. “She had kept one of my traditional garments from when I was eight years old. It looks so tiny now!”

It brought to mind how Dolapo’s fascination with fabrics and their stories began. “For notable occasions, a special kind of patterned fabric is worn, which is woven rather than printed,” she says. “It is known as Aso-oke and came in three varieties:

- Sanyan, woven from the beige silk obtained locally from the cocoons of the anaphe moth, which is worn for weddings or funerals

- Alaari, woven from magenta waste silk, which is worn for festivals; and

- Etu, a deep blue, indigo-dyed cloth, the rarest and most expensive shade, for events such as royal coronations. Etu means guinea fowl, and the cloth is said to resemble the bird’s plumage.

I remember marvelling over that as a child, how everyone knew what to wear when and understood the significance of every piece of fabric.” Storytelling through textiles – a fabulous way to add some magic, print and colour to your next sewing project!

Find out more about Dolapo’s fabrics

Discover her beautiful collection of fabrics and shop for prints and patterns at www.urbanstax.com

A brief guide to African fabrics

Dolapo stocks and sells three main specific varieties of African fabrics. Here she takes us through their production methods and uses.

Ankara

“This is a printed cotton textile with origins in Indonesia, the Netherlands and England,” says Dolapo. “The bright colours and bold patterns have been wholeheartedly adopted by West Africans and is worn for both formal and casual occasions.”

Aso-Oke

“Pronounced ah-SHOW-kay, this is short for Aso Ilu Oke, which means clothes from the up-country,” Dolapo explains. “It’s a hand-loomed cloth woven by the Yoruba tribe of south-west Nigeria and is usually worn for coronations, festivals, weddings, funerals, engagement parties, naming ceremonies and other important events and special occasions.”

Adire

“Pronounced ah-d-reh, this is the name originally given to indigo dyed cloth made by Yoruba women in south-western Nigeria,” says Dolapo. “The techniques used to create the organic and distinct patterns include folding, stitching and threading before dyeing, similar to shibori techniques in Japan.”