Every Autumn, this world-famous Jane A. Stickle Quilt (pictured above © The Bennington Museum) goes on display at Bennington Museum in Vermont, USA. Here we explore the quilt's history and enduring popularity.

Main image (above): Details from the corner of the Jane A Stickle Quilt © The Bennington Museum

A quilting phenomenon

Made in 1863 during the American Civil War by Jane A Blakely Stickle (1817-1896), this sampler quilt is made up of 169 miniature blocks.

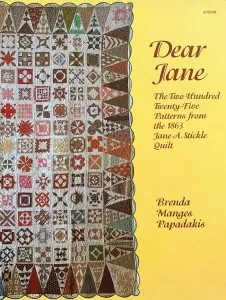

Its allure has yielded close to 140,000 sales of Brenda Papadakis’ book Dear Jane: The Two Hundred Twenty-Five Patterns from the 1863 Jane A. Stickle Quilt and the Dear Jane Board on Pinterest has over 25,000 followers displaying tribute quilts made in every colourway imaginable using reproduction Civil War fabrics to batiks, striking red and white combinations and even fabric lines by Kaffe Fassett and Tula Pink.

- See the quilt on display at the Bennington Museum, Vermont, USA

- Visit the Dear Jane website to sew your own Dear Jane quilt

But what is it about the quilt that has piqued the interest of so many? We spoke to experts from the Bennington Museum where the quilt resides, along with Pam Weeks from the New England Quilt Museum and Brenda Papadakis, and discovered more about this quilting phenomenon. As you will learn, it is a fascinating story of a quilter who, despite the struggles of war, illness and impecunity, produced a quilt of great beauty and character, which continues to excite and unite quilters around the world.

“I strongly believe that a ‘real’ quilter’s life is not complete without seeing it in person.”

Pam Weeks, Binney Family Curator of the New England Quilt Museum

Bennington Museum

The quilt permanently resides at the Bennington Museum in Vermont. Every year it goes on display for a full month so that quilters can experience the impact of this stunning sampler up close and personal, and for 2018 it will be on display from 1 September through to 8 October.

Brought to the museum 60 years ago, the Jane Stickle Quilt is only shown for a short time each year due to the fragility of the fabric. We are very grateful to the Bennington Museum for kindly allowing Today’s Quilter to share the interpretation panels for the quilt from recent exhibitions.

The Maker

Jane Stickle was born Jane Blakely on 8 April, 1817 in Shaftsbury, Vermont. Married to Walter Stickle sometime before 1850, they did not have a family of their own. They did, however, take responsibility for at least three other children in the area.

In an 1860 census, Jane Stickle was listed as a 43 year-old farmer living alone. She eventually reunited with her husband, but during that time alone, she lovingly created what is now known as the Jane Stickle Quilt. As a reminder of the turbulent times the country was going through, she carefully embroidered “In War Time 1863” into one corner of the quilt (pictured below).

The Quilt

Jane Stickle’s hugely ambitious quilt is unique among mid-nineteenth-century American quilts. Sampler quilts, comprised of numerous equally sized blocks each in a different pattern, were fairly common during this period. However, each block was typically pieced by a different person, who often inscribed their contribution with their name and sometimes a date, location or short message.

The small size and sheer quantity of the uniquely patterned blocks in Stickle’s quilt is especially notable. The average size of a quilt block during this period was eight to 12 inches square, while the blocks in the Stickle quilt are smaller than this. Many of the blocks are intricately pieced, the individual pieces ranging in size from less than a quarter of an inch to two inches on a side and some of the blocks having as many as 35 to 40 pieces. Many of the block patterns are commonly seen in quilts from this era, however, many more are unique, drafted by a skilled needle worker with a mastery of geometry.

The design

Each block in the quilt is pieced with two fabrics, a printed calico or even-weave gingham and a plain white cotton. The calicos were carefully arranged by colour in the layout of the quilt. Jane placed a green block in the centre, and chose this block carefully – the only other green blocks are in the outermost corners, along with a blue block.

This centre green block is surrounded by others pieced in yellow and those in turn by alternating concentric rounds of colour including purple, pink and reddish brown calicos. Amazingly, none of the printed fabrics are used in more than one block. Each block uses a unique fabric. Jane’s access to such a wide range of textiles supports the notion that at the time it was common practice for women to trade fabrics for their sampler quilts.

Jane recycled a linen sheet from her mother, Sarah Blakely, for the majority of the quilt’s backing; the initials “SB,” are embroidered in tiny cross stitches on one of the scallops at the quilt’s back edge, originally intended to identify the linen’s owner.

Find out more at benningtonmuseum.org

Read more about quilting heritage

Dear Jane

Brenda Papadakis is the author of the Dear Jane® book which has sold a staggering 140,000 copies. (Dear Jane is the trademark of Brenda Papadakis and is used here with permission). Brenda has written two other historic quilt books: Dear Hannah, in the Style of Jane A Stickle and Susanna Culp 1848. When she saw Jane Stickle’s quilt in Richard Cleveland and Donna Bister’s book, Plain and Fancy, she was captivated by the geometry of Jane’s blocks. At the time, she was teaching Amish, Japanese and Baltimore styles of quilting.

With the help of Barbara Brackman’s publications on block design, she was able to establish that only 30% of the blocks were based on traditional designs, the remaining 70% were unique to Jane and her quilt. In 1992, Brenda and her grandson Ben travelled to Vermont to examine the quilt in detail. She spent three mornings tracing the blocks in the quilt and three afternoons tracing Jane’s life. In October of that year, she went back to the museum to trace the triangles and corner kites of Jane’s quilt.

Get the book & sew your own Dear Jane® quilt

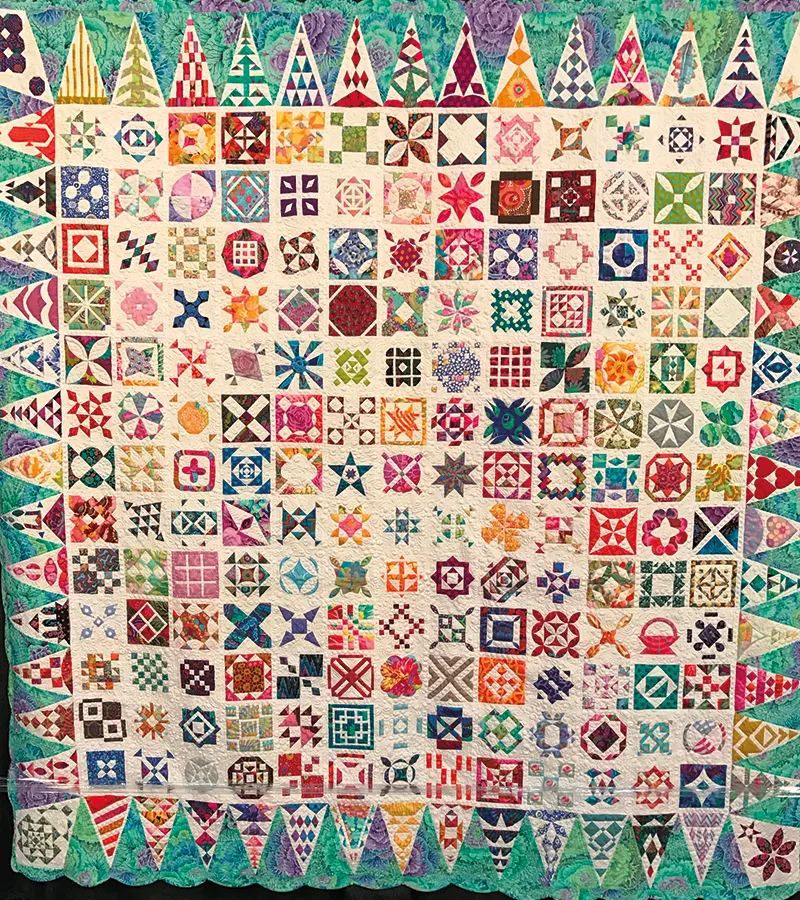

Brenda’s book, the Dear Jane software with twelve lessons for making the quilt, and acrylic templates are all available on her website www.dearjane.com. While you are there, you will discover a wealth of information about making the quilt and the Dear Jane community. We are thrilled to include pictures from the book’s 20th Anniversary Exhibition held in Houston last Fall.

For five years Brenda travelled to Vermont studying Jane’s life and her quilt, teaching techniques for making the quilt and sharing stories of Jane and her life and times. Brenda’s book, Dear Jane: The Two Hundred and Twenty-Five Patterns from the 1863 Jane A Stickle Quilt was published in 1996.

“Jane Stickle’s quilt is more than geometry. It is non-traditional, creative, innovative, even avant-garde if you wish. It is new and exciting, not only in the originality of design but also in composition. From the smallest shape to the larger blocks and triangles, for me the arrangement is pure melody,” says Brenda.

Speaking to Brenda, 20 years on, her sheer delight at discovering the quilt and learning so much about it is as apparent today as it was all those years ago. She has had a second career researching, teaching and travelling throughout the world and has fostered a network of followers in over 35 countries that has evolved into a global community of “Janiacs”. “I feel very blessed to have shared this extraordinary quilt and see myself as something of a messenger in a worldwide quilting bee that is all about unity, solidarity and sisterhood.”

Her firm belief is that Jane Stickle set about making her quilt as a means of bringing some sense of order into a world that was fraught with uncertainty as the American Civil War raged. She couldn’t control what was going on in the world but she could take 5,602 fragments of fabric and piece them together to create something that was beautiful and lasting.

Dear Jane: An Out of Hand Experience by Bonnie Rowbottom, quilted by Sharon Blackmore, on display at the 2016 International Quilt Festival in Houston.

Further study

Pam Weeks is the Binney Family Curator of the New England Quilt Museum in Lowell Massachusetts. Her research into the Jane Stickle quilt, in conjunction with the Bennington Museum, has provided invaluable information about Jane’s personal circumstances and how the quilt came to be.

Pam herself started making quilts as a result of the craft revival inspired by the American bicentennial in 1976. Like many of her peers, she made traditional quilts with the limited fabrics available. By the mid-1980s she was designing her own work and developed as an art quilter, heavily influenced by the work of Nancy Crow. “In 1991 I meandered down a different avenue when I took a class on reproducing the antique quilts I loved but couldn’t afford, and since then I’ve been hooked on quilt history.”

We asked Pam about her current role and her research into Jane Stickle…

Tell us about your role as Binney Family Curator at The New England Quilt Museum.

“I am thrilled to have found the job of a lifetime at the end of my fifth decade of life. As the Binney Family Curator of the New England Quilt Museum, I primarily organise and implement the exhibition schedule for our three main galleries. Travelling around the country to major quilt exhibits and doing online research for ideas, as well as winnowing exhibition proposals, provides me with more ideas than I have space to use! I am also responsible for our collection of nearly 500 antique and contemporary quilts and related items. We rely on our volunteers for support in all of these areas.”

You’ve become something of an expert on the history of The Jane A. Stickle Quilt. Can you tell us more about your first encounter with the quilt and what caught your interest?

“The Jane A. Stickle Quilt is probably one of the most famous quilts in America, if not the world. It captured the hearts and imaginations of quilters around the globe because of Brenda Papadakis’ book Dear Jane, with its warm and imaginative romanticising of Jane Blakely Stickle’s story and the making of this extraordinary quilt. More than 140,000 copies of the book have sold around the world, and very nearly every quilt show I’ve attended has at least one Dear Jane quilt on exhibit, if not an entire row or mini-exhibit of many reproductions of the quilt itself.

“My first viewing of the quilt was like that of most people seeing it for the first time. It is literally awesome, and that first visit is a form of a pilgrimage; I strongly believe that a ‘real’ quilter’s life is not complete without seeing it in person. The quilt is a masterwork of piecing and composition and it was amazing to be invited to do deeper research, to examine every aspect of it and then to write about it.”

Tell us about the discoveries you made

“My research, substantially aided by the curatorial and library staff at the Bennington Museum, revealed some more details about Jane’s life than previously published. I was concerned about being able to find anything, as I have attempted research on other middle- and working-class quiltmakers from the mid-nineteenth century and understood how little information was available. As a team we found some important ephemera, including the household inventory of Jane’s father who died when she was 13. It documented an above average farmer and carriage builder’s home with multiple sets of linen sheets, chairs, dishes and quilts. We learnt that Jane’s education was provided for by her father, and we assume she attended one of the academies in the area.

“The listing of the linen sheets was an important find, because one of them was used by Jane to back her quilt. Tiny cross stitched initials appear on the back of the quilt—‘SB’ for Sarah Blakely, Jane’s mother.

“Curator Jamie Franklin made what is probably the most important research finds. It was an article from the Bennington Banner that reported highlights of the county agricultural fair. ‘…Mrs Stickles [sic] presented…a very extra fine bed quilt. Mrs Stickles is an invalid lady, having been for a long time confined to her bed, but her ambition to do something to kill the time induced her to piece this quilt. It contains many thousands of pieces of cloth, no two of which are exactly alike. Upon one corner is marked in plain letters, ‘made in the war of 1863.’”

The museum notes that ‘A week later, on 8 October, the Bennington Banner published a list of premiums awarded at the fair. In the “Ladies Section” it is noted that the “Best patched quilt” was awarded to “Mrs. W. P. Stickles” with a prize of $2, equivalent to about $40 in today’s money. Though modest in comparison to her remarkable accomplishment, it is nice to know that Stickle’s quilt was recognised by her contemporaries, and that it continues to inspire.’

We also unearthed some documents that explained the Stickles’ financial failure that led to them becoming wards of the town. Town documents revealed that they lived in poverty, “kept” by a David Buck, who was probably a distant relative.

If you could travel back to 1863 and spend some time with Jane, what would you ask her?

“Did you draw the piecework patterns yourself? Did you have children? Where are the rest of your quilts?”

And last but not least, have been tempted to make your own Dear Jane quilt?

“Never!”

Pam is the author of Civil War Quilts, Schiffer Publishing Ltd (2012). You can discover more about her passion for quilts by visiting her website www.pamweeksquilts.com or find out more about the New England Quilt Museum at www.nequiltmuseum.org.